The Tetrarchy Explained: Creation, Functioning and Collapse

A bold Imperial experiment to stabilize the crumbling Roman Empire

Image Source: Wikipedia, Coppermine Photo Gallery, CC BY-SA 3.0

On May 1, 305 AD, in an act unprecedented in Roman history, two emperors — Diocletian and Maximian — voluntarily laid down their imperial powers.

In twin ceremonies held at Nicomedia in the East and Milan in the West, they removed the purple robes from their shoulders and stepped aside, not under pressure of revolt or illness, but as part of a meticulously planned transition. They had ruled not as rivals but as partners, and now they would retire in the same spirit, making way for their chosen successors.

It was the high point of a bold political experiment known as the Tetrarchy, or “rule of four.” For over a decade, Rome had not one emperor but four — two senior rulers (Augusti) and two junior ones (Caesares) — governing different regions of the vast Roman Empire in concert. It was an audacious solution to a century of chaos, civil war, and imperial assassination.

The Tetrarchy promised order, stability, and succession without bloodshed. But though its design was ingenious and sound, it was built on fragile foundations: the loyalty of men, the illusion of unity, and the hope that personal ambition could be restrained.

Within a generation, it would unravel — but its legacy would shape the empire forever.

Origins and Motivation: A Century of Crisis

By the time Diocletian came to power in 284 AD, the Roman Empire had endured half a century of instability and fragmentation. Historians refer to this period as the Crisis of the Third Century — a time when emperors rose and fell with dizzying speed, more often than not meeting violent ends.

The young Severus Alexander, whose death is today regarded as the start of the crisis, was killed by his own soldiers, as was his successor, the brutal soldier Emperor Maximinus Thrax. The teenage Emperor, Gordian III, died under suspicious circumstances, either killed by his men or by the Persians.

The unfortunate Emperor Valerian was captured alive by the Persians and according to some sources, lived out his last years in humiliation, being used as a footstool by King Shapur I. Emperor Claudius II died of plague, while the capable Aurelian, the man who reunited a disintegrating Roman world fell victim to the machinations of one of his secretaries, while old Emperor Carus supposedly was struck dead by lightning ( or just the blades of some of his men).

The list is quite a bit longer as between 235 and 284, more than two dozen emperors claimed the throne, many for only months at a time.

The empire split reunited, and nearly collapsed under the weight of civil war, economic collapse, plague, and external invasions from Germanic tribes, Persians, and others along its vast borders.

Violence, however, was not reserved against the person of the Emperor only, as men fighting for the purple could be just as violent against their rivals. When Diocletian seized power, his first act was to stab to death the influential Aper, a man whom he accused of murdering his predecessor.

By then Diocletian was a seasoned soldier, who witnessed the rise and fall of several Emperors, and he also came to understand that no single man — no matter how capable — could govern an empire that stretched from the Atlantic to the Euphrates, as with threats rising on multiple frontiers, Emperors needed to delegate command, a necessity that raised one serious question, however.

What was to stop commanders leading huge armies from turning against their master and claiming the purple for themselves?

Diocletian’s solution was revolutionary: share power at the top. By dividing the empire into manageable zones and assigning co-rulers to govern them, he hoped to eliminate rivalry and create a legitimate imperial presence in all the troublesome frontier zones, speed up military responses, and create a structured, more peaceful system of succession.

The Tetrarchy was born not out of ideology but necessity — a calculated effort to impose order on an empire that had forgotten what stability looked like.

A portrait of the Four Tetrarchs, brothers in arms very much. Image Source: Wikipedia, Nino Barbieri, CC BY-SA 3.0

Structure of the Tetrarchy — Four Rulers, One Empire

Just how well thought out the Tetrarchy was is a matter of debate, as whether the system came about thanks to a well laid out plan or was the result of more ad-hoc measures building on each other is not entirely clear.

Whatever the truth, however, once it was formed, the system was designed with rigid clarity and imperial symmetry.

At its core were two senior emperors, the Augusti, who held supreme authority. Each Augustus appointed a Caesar, a junior partner groomed for succession. These four men ruled distinct regions of the empire but were expected to govern in harmony and coordination. Their titles reflected a chain of command, not separate sovereignties — in theory, Rome remained a single empire, united by a shared purpose, and the Emperors could intervene in the territory of their co-rulers, like Galerius campaigning against the Persians in the late 290s, while Diocletian was occupied with quelling an attempted usurpation in Egypt.

Diocletian retained control of the East, ruling from Nicomedia, while his co-Augustus, Maximian, governed the West from Mediolanum (modern Milan). Their Caesars were men of proven military ability: Galerius, serving under Diocletian in the Balkans, and Constantius Chlorus, assisting Maximian in Gaul and Britain. This geographic arrangement allowed each emperor to be close to the empire’s most vulnerable frontiers — along the Rhine, the Danube, and the Persian border.

The Tetrarchs shared military responsibilities, administrative oversight, and judicial authority, but they were also bound by a powerful image of unity. They issued coins bearing similar portraits, dressed identically in public ceremonies, and were often depicted standing shoulder-to-shoulder in statues and reliefs — indistinguishable, co-equal, and inseparable. Diocletian and Maximian even arranged family ties, strengthening bonds through marriage alliances.

And for a time, the new system worked well enough. The empire, though divided in administration, stood firm in purpose. But that unity would not survive the men who created it.

Successes and Early Stability — A Rare Peace

For a brief but remarkable period, the Tetrarchy delivered on its promises. The empire, long wracked by rebellion and external assault, experienced a renewed sense of order, security, and confidence. Each ruler focused on their assigned region, responding swiftly to threats and restoring imperial authority in places that had drifted beyond Rome’s control.

Constantius Chlorus led successful campaigns in Gaul and Britain, defeating the usurper Carausius and his successor Allectus, and restoring the island to imperial rule.

In the East, Galerius won a decisive victory over the Sassanid Persians at the Battle of Satala in 298, forcing a favorable peace that expanded Roman influence in Armenia and Mesopotamia, while at the same time, Diocletian quelled another usurpation attempt in Egypt.

It would be an exaggeration to suggest that the Tetrarchy abolished civil war, and in fact, the rise of Carausius may have been the cause of the elevation of Constantius. Nonetheless, considering some of the worst periods of the third century, by sticking together the Tetrarchs managed to limit usurpation attempts.

Internally, Diocletian and his colleagues undertook sweeping reforms of the military and bureaucracy. Army structures were reorganized to allow faster deployment along the frontiers, while new provincial divisions and tax systems sought to bring efficiency and oversight to local governance. These reforms, again were not necessarily the brainchild of the Tetrarchs, but processes that were already underway, but even so, the Tetrarchs made sure that the process continued, leading to the strengthening of the Roman state.

But beneath the surface, ambition simmered, and the carefully balanced structure depended entirely on the personal discipline and cooperation of its emperors. The moment that unity cracked, the entire system began to collapse.

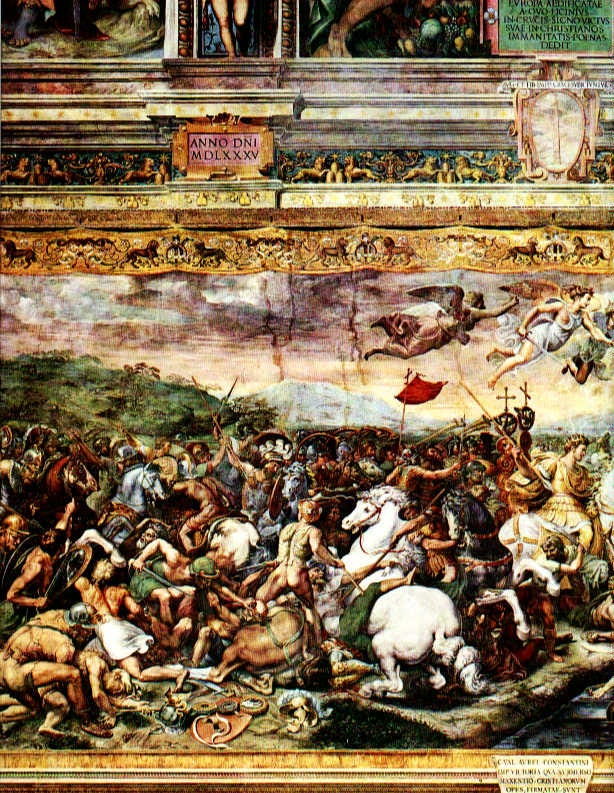

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, where Constantine famously defeated Maxentius, was one of the pivotal moments of the civil wars that broke out shortly after 305 AD. Image Source: Wikipedia, Raphael

The Collapse of the Tetrarchy — Ambition Undone

The Tetrarchy was built on discipline, hierarchy, and controlled succession — but it rested on a fragile assumption: that every emperor would accept his place and wait his turn. That illusion shattered almost immediately after Diocletian and Maximian abdicated on May 1, 305 AD.

In theory, the Caesars, Galerius, and Constantius Chlorus, smoothly ascended to the rank of Augustus. Galerius, now the most powerful man in the East, handpicked two new Caesars: Maximinus Daia, his own nephew, and Severus, loyal to Galerius, But the personnel of the second Tetrarchy was born under a cloud of resentment, and it made almost certain that it was not to last for good.

According to the contemporary writer Lactantius (who also worked first for Diocletian and later for Constantine in the imperial palace), initially Diocletian disapproved of both the two new Caesars, and in a conversation with Galerius he suggested that these roles should rightfully be occupied by Maxentius and Constantine, the sons of Maximian and Constantius.

Diocletian, however, went even further and called Severus a drunkard, a man for whom day is night and night is day. Yet, under pressure from Galerius, Diocletian eventually relented and agreed to the succession of Severus and Maximinus.

Galerian got his way, and his loyalists became the new Caesars, but whether the armies these men were to command would accept them or not was still a question only time was to answer. As was the question of how would the two overlooked sons react to the decision that simply overlooked them.

The empire did not have to wait for long to find out.

When Constantius Chlorus died unexpectedly in 306 while campaigning in Britain, his troops declared his son Constantine as emperor — a move outside the Tetrarchic system. Around the same time in Rome, Maxentius, the son of the retired Maximian, seized power with senatorial backing. Suddenly, there were more two new emperors, each claiming legitimacy, with Galerius struggling to reassert order, as even old Maximian moved out of retirement and tried to reclaim power once more, clashing with both his son and Constantine in short succession.

From 306 to 324, the empire descended into a prolonged civil war. Alliances shifted, emperors fell, and the idea of shared rule disintegrated. By 312, Constantine marched on Rome and defeated Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, a turning point both militarily and religiously. Two years later, he turned on his remaining sole rival Licinius, ultimately defeating his last opponent for good a decade at Chrysopolis in 324.

With that victory, Constantine became sole ruler, ending the last remnants of the Tetrarchy and laying the foundations for a new era of imperial rule — one centered on dynastic succession, Christian patronage, and a capital soon to be called Constantinople.

Legacy and Historical Significance — An Experiment That Shaped an Empire

Though the Tetrarchy ultimately failed to prevent civil war or ensure peaceful succession, it was still an interesting experiment, though one that ultimately may have been destined for failure from the get-go. Nonetheless, some of its innovations were there to stay.

First, it demonstrated that the empire could be effectively administered from multiple centers, a concept that would endure. Later Roman emperors — especially in the East — continued the practice of ruling from strategically located capitals like Nicomedia, Sirmium, or Constantinople rather than the old senatorial heart of Rome. In fact, Rome itself faded in political relevance, a trend accelerated under Constantine.

Second, the Tetrarchy established many of the ceremonial and bureaucratic features of later Roman and Byzantine rule. Emperors became more remote, exalted figures — surrounded by elaborate court rituals and divine symbolism. The notion of the emperor as a quasi-sacred, stabilizing figure was reinforced in architecture, coinage, and imperial iconography. Not coincidentally, historians used the start of Diocletian’s reign as the start of a new era of Roman history, the Dominate.

Third, it laid the groundwork for the eventual division of the Roman Empire. While Diocletian insisted on unity, his administrative division of East and West anticipated the later permanent split between the Western and Eastern Roman Empires.

In the end, the Tetrarchy was a noble failure — a creative, well-crafted solution to an age of anarchy, undone not by bad design but by the very human ambitions it tried to contain. And yet, in failure, it helped forge the future of the empire.

Sources

Adrian Goldsworthy (2010). The Fall of the West: The Death of the Roman Superpower. Yale University Press

Peter Heather (2005). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press.

Lactantius. On the Deaths of the Persecutors.

Taking one emperor and dividing his power by four was a terrible idea. If there was a desire to have an imperial representative in every part of the empire that was on the front lines then there are ways to do that that don't require multiple emperors.

People who want to violently seize power have four times as many options as previously, and there will always be an Augustus or Caesar in their region. And if you subtract the battle casualties from every time an Augustus fought an Augustus for control of the whole empire, or when a Caesar thought they were good enough to be an Augustus, then the Roman army would have been much stronger and the West much less likely to have fallen.