The Revolutions of 1848 Explained: Causes, Events, and Consequences

A Year that Rocked a Continent

The revolution in Berlin. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

The course of history, at times, has a cyclicity that witnesses the rise and downfall of states, and empires, and the ideas or ideologies that accompanied these entities get challenged and even overthrown.

Yet this cyclicity is very hard to predict at times, as when historians go through the correspondence of contemporaries, we quickly figure out that few had any idea of the upcoming cataclysm.

Such was the case in January 1848 also, when the brilliant French historian Alexis de Tocqueville warned his fellow deputies in the French Parliament that right now they were sitting atop a volcano, but his warning was brushed aside. The self-confidence of the French deputies, however, was shattered a month later when the Parisians rose against the monarchy and plunged the City of Lights into chaos.

In 1848, however, the revolution was not limited to France only. Still, one by one, revolutions broke out in Vienna, Milan, Venice, Budapest, Berlin, Bucharest, Palermo, and other smaller cities also to create a crisis that threatened to turn the political status quo of the entire continent on its head.

The question we can ask is why? Why was the Europe of 1848 such a sleeping volcano?

Prelude to 1848

By 1848, nearly sixty years had passed since the 1789 Revolution of France, and thirty-three years had passed since the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte, leaving Europe in the grasp of a conservative-absolutist alliance that is now remembered as the Holy Alliance, made up of the Russian Empire, the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia.

Coming out defeated from the Napoleonic Wars, France was forced back to her 1792 frontiers and found herself ruled again by the Bourbon dynasty that was toppled in 1792. Yet the defeat of Napoleon was not enough to turn back the clock in France, and the newly restored French monarchy was to be a constitutional monarchy that maintained the Napoleonic status quo inside the country.

The final great power of Europe was Great Britain. Safe on her island, Albion was not particularly interested in the old continent so long as no player strong enough to dominate the continent (and challenge the British overseas empire) was likely to emerge.

Despite the defeat of the Emperor at Waterloo, the new conservative order was rocked by many crises in the 1820s, with revolutions breaking out in Spain, the Italian states, Greece, Poland, France, and Belgium. Not all of these revolutions were successful, yet the upheavals were significant so much as they showed that the existing status quo was far from universally accepted.

In France, the Bourbons were overthrown again in July 1830, though the constitutional monarchy was preserved with Louis Philippe, the King’s cousin, taking the throne and implementing a slightly more liberalized regime. The fall of the Bourbons and the inability of the Holy Alliance to do anything about it was a heavy blow for the conservative order and left Europe west of the Rhine virtually out of their grasp.

Yet if the Holy Alliance worried that France may attempt to reconquer Napoleon’s former empire, their worries were to be unfunded, as the new regime of France was content to remain at peace with them and even refused to send aid to the Poles, who at the time were in open rebellion against Russia.

Even without a French military revival, however, these regimes were still anxious as they were well aware that their own populations began to question the legitimacy of the current political status quo.

Most articulate and well-organized were the liberals of the age, members of the rising middle class, reform-minded nobility, army officers, and the liberal professionals who wanted to implement reforms that would have promoted constitutional government, freedom of speech, and equality before the law, though not necessarily universal electoral franchise just yet.

The landscape of the continent was also rapidly changing as from the 1830s onward, the industrial revolution that first arrived in Britain began to spread to the mainland. With the population of the continent rising very rapidly, the new industries had no shortage of labor, and in fact, such was the growth of the population that the economy struggled to integrate all the new hands.

As one witty contemporary sarcastically said: “There were twenty times more lawyers than suits to be lost, more painters than portraits to be taken, more soldiers than victories to gain, and more doctors than patients to kill.”

The rising new industry, in turn, threatened the livelihood of traditional artisans and craftsmen, who struggled to compete with the speed and low prices of industrial works pumping to the market.

The rapid growth of the population put heavy pressure on the countryside also, and when bad weather spoiled the harvests, starvation was the outcome. The worst hit was Ireland, where the Great Famine caused the death of approximately one million, but the rest of the continent also struggled to adequately feed its population in the 1840s, years that have become known as the Hungry Forties.

Thus, as the calendar was turning 1848, de Tocqueville’s observation was more than precise, as Europe’s old order was facing the uneasy but formidable alliance of disgruntled liberals, angry workers, and hungry peasants. All the continent needed was a spark to explode.

The springtime of the people’s

The first signs of what was to unfold came in January when the Bourbon troops were expelled from Sicily. When King Ferdinand sent reinforcement from Naples, he left his forces on the mainland weakened, and new uprisings broke out in Naples. Fearing that he was about to lose his throne to revolution, Ferdinand then pre-emptively agreed to make concessions to defuse the situation.

His example, in turn, was followed by many princes in Italy, who agreed to grant concessions, usually in the form of a constitution and the arming of a middle-class national guard to protect property in the cities and towns.

The chain of events in Italy was probably worrying enough for Europe’s absolute rulers already, but the moment when the 1848 revolutions truly took off was in February when the revolution spread to France.

Earlier in the century, Metternich, the arch-conservative chancellor of Austria, remarked that when France sneezed Europe caught a cold, and 1848 was to prove him right again.

Though France remained a constitutional monarchy all the way to 1848, the franchise that elected the Legislative Assembly was no more than 0,5% of the population, significantly fewer people than in the 1791 or 1795, not to mention the 1793 constitutions of the French monarchy or republic had. The arrogance of Louis Philippe’s minister, the brilliant historian Francois Guizot, did not help the case of the July Monarchy either, as when confronted about the limited franchise that allowed only the richest strata of French society a political voice, Guizot coldly replied enrichissez-vous, get rich.

Had the July monarchy had a bigger popular base, it may have survived the February uprising of 1848, but when confronted by mobs of angry Parisians, the loyalty of their troops was questionable. The professional troops were deemed mostly reliable, but they made up only a fraction of the government’s forces in Paris as the majority were made up of the national guard, who either refused orders or outright joined the rebels.

Unable to hold the capital, Louis Philippe was advised by Adolphe Thiers to retreat from Paris for now, gather more troops from the provinces, and crush the uprising through brute force. The old King, however, was hesitant, and when General Bugeau estimated the fighting could cost the lives of as many as 20,000, he lost his heart and decided to abdicate.

King Louis Philippe abdicated in favor of his grandson, but it was not to be, and on the steps of the Hotel de Ville, the famous poet Lamartinne proclaimed the republic.

Thanks to the new telegraphs, the news of the fall of the French monarchy spread rapidly throughout Europe, unnerving the courts of Vienna, Berlin, and Saint Petersburg. When he got news of the revolution in Paris, Tsar Nicholas II is said to have burst into a ball and exclaimed, saddle your horses, gentleman, a republic has been proclaimed in Paris.

Russia, with its limited middle class and non-existent working urban class, remained immune from the revolution in 1848, but a few weeks after the upheaval of Paris, the revolution began to spread to the Austrian Empire and Prussia.

With uprisings breaking out all over the Austrian Empire, the Habsburg court was on the defensive as its troops struggled to contain the uprisings in Veneto, Lombardy, and Vienna, forcing Emperor Ferdinand’s ministers to sacrifice Metternich, who was sent into exile and gave concessions. Using the upheavals to their advantage, the reform-minded leaders of Hungary traveled to Vienna and received the blessing of the Emperor to implement their own reform program in Hungary, turning Hungary into an independent entity within the empire.

In Italy, the situation of the Habsburgs turned from bad to worse when King Carlo Alberto of Savoy decided to use the anti-Austrian uprisings to invade Lombardy in an attempt to unify Italy under the banner of his own kingdom.

Terming the campaign as an anti-Austrian Crusade to liberate Italy, Carlo Alberto secured the reluctant support of the other Italian states, but the Austrians were not defeated just yet. Under the command of the formidable Marshal Radetzky, an 80 years old veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, the Austrian forces fell back to the Quadrilateral ( the fortresses of Legnago, Verona, Peschierra, and Mantua) and were awaiting the arrival of the Savoyards and Italian volunteers.

Mere days after the outbreak of fighting in Vienna, the streets of Berlin also turned into a battlefield as workers, craftsmen, and students erected barricades and clashed with the Prussian army. Sickened by the sight of his soldiers slaughtering his subjects, King Frederick William agreed to make concessions and recalled the army to the barracks.

Uprisings also broke out in Habsburg and Prussian-controlled Poland, but the challenge of revolution was staved off by the use of force and timely abolition of serfdom in Galicia, a move that severed the ties of the revolutionaries from the peasantry.

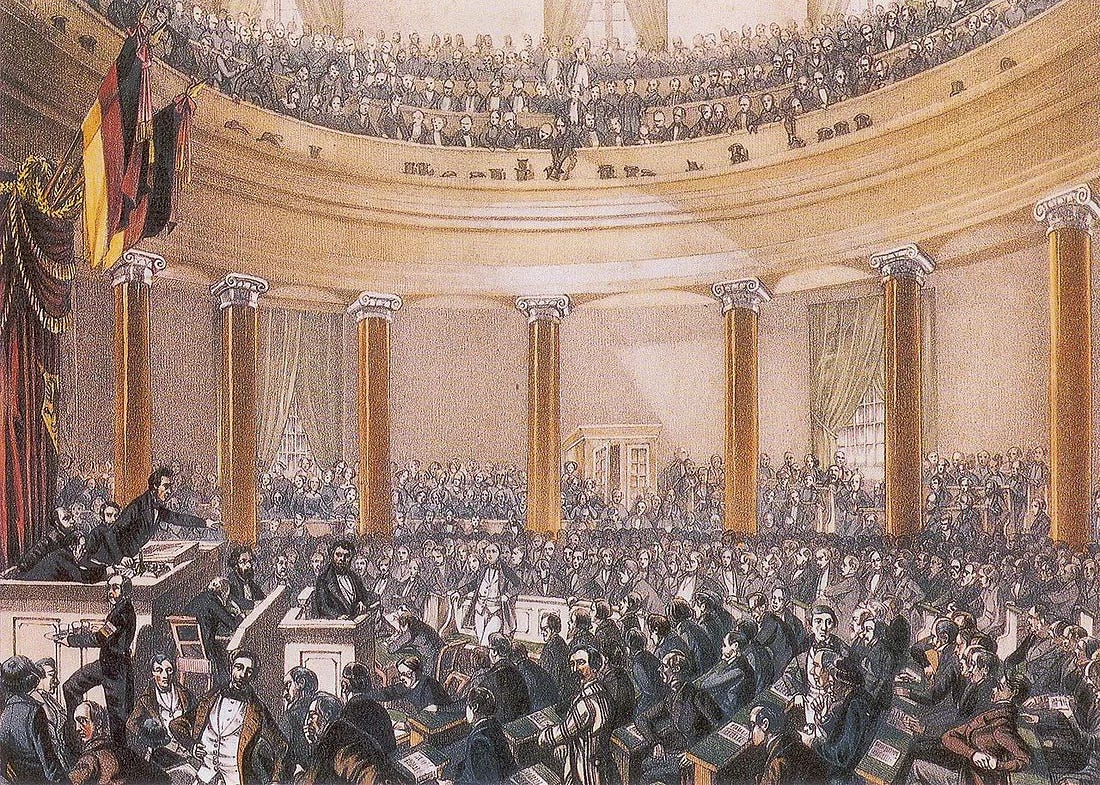

To pre-empt revolutions, the smaller German states all agreed to grant concessions in the spring of 1848, and elections were held for the first pan-German Parliament, the Frankfurt Parliament, which began its first session on May 18, 1848, and was tasked to write the constitution of a unified German Empire.

The events of the spring caught the old regimes of Europe off guard. The monarchy of France was toppled altogether and replaced by the republic, while other monarchs managed to preserve their throne by giving in to the demands of the people. But shaken as the old order was, dead it was not yet, and as the divergent forces that created the revolution began to divide among themselves, the old order received its chance to fight back in the summer of 1848.

The June Uprising in Paris, the moment when the French revolutionary left and right became split. Image Source: Horace Vernet, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

The revolution under siege

Elections throughout Europe were held in the aftermath of the revolutions, and the results immediately succeeded in splitting the revolutionaries. In France, a conservative liberal and to a lesser degree monarchical, National Assembly was elected, which in May agreed to dissolve the public workshops created earlier in the spring to alleviate the lot of the poor and unemployed.

A few weeks later, another huge uprising broke out in Paris, but this time round, the government’s forces put down the uprising through force, the four days of fighting costing lives more than 4,500 killed, and several thousand more wounded. The suppression of the June uprisings put an end to the fear of social revolution in France, and the republic took a decisive conservative turn afterward.

Amid the chaos, an old name also got his chance to shine again. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of the Emperor, returned to Paris in the aftermath of the revolution and was elected to the National Assembly in the spring. Though largely looked down upon by the elite of France, who regarded him as a buffoon, Louis Napoleon, in no small part thanks to his name, became an instant hit with the masses, and in December, he was elected as the first President of France, taking more than 70% of the votes. Yet, his populist image was more a facade than anything else, as Napoleon began to appoint liberal monarchists, rather than republicans or socialists, into his cabinet, while in terms of his foreign policy, Napoleon decided to support measures that would gain him the support of French Catholics.

In Italy, Austrian field Marshal Radetzky gathered a great army in the spring, and while King Carlo Alberto’s forces were bogged down besieging fortresses, the old Field Marshal finally took the initiative in June and went on the offensive and defeated the Piedmontese at the Battle of Custoza. Defeated, the King was forced to retreat and called for an armistice, an offer accepted by Radeztky.

Though the Austrians could have continued their advance further west and overrun the Kingdom of Savoy, the wily old soldier also had a good political sense and wagered that further Austrian victories would lead to conflict with France. Radeztky’s judgment was proven inch perfect, as shortly after news of Custoza reached Paris, the French government held a session on whether they should intervene in northern Italy. For the moment, they refrained, but the decision was only taken through one single vote at the time.

Further south in Naples, already in May, King Ferdinand was making plans to turn back the clock and regain power, but for the moment, he hesitated, but once news of Custoza reached him, he deemed the moment ripe for action and using the army he dissolved the Parliament and nullified the concessions he granted earlier. An army was dispatched to Sicily also to reconquer the island for the Bourbon monarchy.

The situation of the revolution was becoming critical in Venice also, as following Radeztky’s victory in the summer, more Austrian troops were diverted against the revolutionaries of Venice, who found themselves besieged by the Imperial troops.

Further east in the Austrian Empire, as the imperial government was gaining confidence, Vienna was beginning to make plans to retake power in Hungary. Unfortunately for the imperials, this task proved to be rather tricky, as, unlike most revolutionary movements of 1848, in Hungary, the revolution managed to take control over the state apparatus, administration, and a significant part of the army, forcing Vienna to plan a possible invasion.

The main force tasked with the invasion was to be led by Croatian Ban Jellacic. On paper, Croatia was in a personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary and thus, legally, should have been under the control of the new Hungarian government, but Jellacic flatly refused to take orders from Budapest.

Tension steadily rose between Vienna and Budapest throughout the summer and early autumn. One final attempt of Vienna to thwart war was made in September, when they sent the Imperial loyalist count Lemberg to Hungary to take command of the army, but shortly after his arrival, an angry mob murdered the count in Budapest.

The Hungarian government probably had nothing to do with the atrocity, and quickly caught and tried the murderers, but it was too little too late.

War was now inevitable.

Yet, not all was going well for the Imperial Court. The advancing force of Jellacic was thwarted at the Battle of Pakozd, while as troops were gathered in Vienna to be sent to Hungary, a revolt broke out in the capital again. The Imperial family was forced to flee for its life, while the unpopular minister of war was lynched by a mob.

Unable to contain the forces of revolution, the government ordered the soldiers to retreat from Vienna and take station outside the walls, where they were to be reinforced by the army of Prince Windisch Gratz, who earlier that summer suppressed an uprising in Prague.

When he received news of what was going on in the capital, Jellacic also began to march westward and arrived under Vienna in October to join the forces of Windisch-Gratz.

After talks of a peaceful resolution to the conflict broke down in early October, the army began to besiege the city. Determined as Windisch-Gratz was to crush the rebellion, the fate of Vienna seemed doomed, the only hope of the Viennese being the Hungarians, who pursued Jellacic into Austria as the Croatians marched out of Hungary. Unfortunately for the revolutionaries, the Hungarians were defeated by Jellacic at the Battle of Schwechat. With the morale of his army badly shaken, General Moga ordered his men to retreat into Hungary.

The defeat of the Hungarians, in turn, sealed the fate of Vienna’s revolutionaries, who were forced to surrender on October 31. Most of the leading figures of the revolution were captured, and many were executed, including Robert Blum, a deputy of the Frankfurt Parliament who arrived only weeks earlier.

The execution of Robert Blum perfectly symbolized the lack of authority the Frankfurt Parliament had over the German monarchies. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Carl Steffeck

With Vienna recaptured, the Imperial government received a new boost of confidence and was making plans to retake Hungary too. Before the Imperial counterattack could begin, the feeble Emperor Ferdinand was forced to abdicate, and his 18-year-old nephew Franz Joseph became the new Emperor of the Austrian Empire. Considering himself unrestrained by the laws signed by his uncle, Franz Joseph in turn disowned the concessions made earlier in 1848.

Habsburg’s advance into Hungary began in the winter of 1848–49 and initially was met with little resistance as the outnumbered Hungarians retreated in front of the Habsburg troops. Due to the slow Austrian advance and rapid mobilization of their own manpower, however, the Hungarians were ready for the counterattack in the spring of 1849, and led by the brilliant general Gorgei, they scored victory after victory in the spring campaign.

By May, Gorgei was ready to recapture Budapest, the capital, however, the military and political leadership of the country were in disagreement by then. The civilian government led by the fiery Lajos Kossuth had declared the country independent in April, much to the disgust of Gorgei, who saw this move as political suicide, which would inevitably prompt an intervention by Russia.

Gorgei also deemed the siege of Buda castle as a waste of time that would lose weeks for his army and advised the politicians to encircle the castle with a smaller force, take the bulk, and move westward against Vienna. On the insistence of the civilians, however, Gorgei was forced to lay siege to Buda and lost three crucial weeks.

While the bulk of the Hungarian force was besieging Buda, Emperor Franz Joseph met with Tsar Nicholas to request military aid. The Tsar agreed, and 200,000 Russians began to invade Hungary from Poland and Wallachia.

Facing an overwhelming numerical disadvantage in the summer, the Hungarian resistance collapsed, and General Gorgei surrendered in August. Despite Russian pleas for clemency, the Court of Vienna was in no mood to be merciful, and several hundred leading political and military figures of Hungary were tried and executed in the following months. On the intercession of the Russians, Gorgei was spared, but this mercy only succeeded in making him look like a traitor in the eyes of many of his countrymen, who went on to accuse him of treason, an accusation that went on to haunt the general until he died in 1916.

The revolution came to an earlier end in Prussia. Following the March uprising in Berlin, King Frederick agreed to make concessions, but during the spring, he left Berlin and retreated to Potsdam. Surrounded by generals and fellow conservatives, the King’s resolve returned, and in December, using the military, he dissolved the Prussian Parliament that was created in the spring. Not all reforms were turned back, however, as the King agreed to grant his kingdom a constitution, but a constitution where he retained executive power and control over the military.

While the revolution was over or in retreat in Prussia and the Habsburg Empire, in other parts of Germany, the divide between the moderate liberal constitutional monarchists and republicans was at boiling point, with some radicals going so far as to launch military attacks against the smaller German states.

The waters of German unity were tested further when conflict broke out between Denmark and the German Confederation over the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, leading to the outbreak of war with the endorsement of the Frankfurt Parliament.

Yet, the impotence of the Parliament was laid bare by their reliance on the princes to send their armies against the Danes, armed forces the Frankfurt Parliament lacked entirely.

The Frankfurt Parliament hoped their constitutional proposal could convince King Frederick William of Prussia to become the Emperor of their envisioned Germany, but in the spring of 1849, the King politely turned down the offer and then sent in his troops to dissolve the Parliament. A series of pro-Frankfurt Parliament uprisings broke out all across Germany in the following period, but the princes, assisted by the Prussians, put down all of these.

Despite the promise of 1848, the Frankfurt Parliament’s attempt to create a new unified liberal Germany ended in abject failure. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Ludwig von Elliott, Public Domain

The cause of the revolution did not fare much better in Italy either. In Rome, revolutionaries drove out the Pope and his loyalists, but the new Roman Republic lasted for only 100 days when the Pope received reinforcement from France to crush the Roman Republic. Though formally France was still a republic, its new President, Louis Napoleon, surrounded himself with monarchists, and in his foreign policy, he took a pragmatic stance of acting to gain the support of French Catholics.

In Lombardy, King Carlo Alberto broke the armistice and attacked again in the spring of 1849, but was defeated again by Radeztky at the Battle of Novara. With victory now out of reach, the King asked for an armistice again in the aftermath of the battle.

The defeat at Novara was the final defeat of Carlo Alberto, who decided to abdicate in favor of his son, fearing that his defeats delegitimized himself and that if he’d tried to cling to his throne, a republican uprising might break out in his kingdom.

With the Kingdom of Savoy defeated, all that was left of the Italian uprising was Venice. The city of lagoons, in turn, resisted heroically until August, but in the end, its leader, Daniele Manin, was forced to concede defeat and surrender.

Aftermath

By the time the year 1849 came to a close, much of what the people of Europe gained in the spring of 1848 was lost, with the absolutist regimes mostly back in control except in France, and even in France, fear of a social revolution led by a political left unnerved the liberals to join with the conservatives and turn the republic more and more conservative, until it was finally overthrown by President Louis Napoleon in 1851, who led a successful coup that toppled the republic and replaced it with the Second Empire.

To use the words of G.M. Trevelyan, 1848 was the turning point at which modern history failed to turn.

In many regards, the statement was true, as few of the rights won in 1848 survived for long, except the abolition of serfdom in the Habsburg lands, universal suffrage in France, and the rather authoritarian constitutions.

Yet, the defeat of the revolution was far from final as the factors that paved the way for 1848 remained as present after 1849 as they were before, factors that forced modern conservative politicians like Bismarck to set up conservative newspapers and clubs to gather public support for conservative politics for example.

The cause of national determination of German and Italian people did not die with 1848 either, and in 1861 and 1871, both Italy and Germany finally became unified nation-states for the first time in their history, though in both cases, the unification was led by monarchists rather than republicans.

National self-determination was granted to the Hungarians also, as following his defeats against the French in 1859 and the Prussians in 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph deemed that a political compromise with Hungary was necessary for the preservation of his empire, turning the Austrian Empire into the Austro-Hungarian Empire, two basically independent political entities united by their ruler the Emperor, who retained control over foreign policy and the armed forces.

Source

Rapport, Michael (2009). 1848: year of revolution. Basic Books.