At dawn on May 29, 1453, the sky above Constantinople turned black — not from clouds, but from the smoke of Ottoman cannons pounding its ancient walls. For 53 days, the city had endured an unrelenting siege. Now, the final assault had begun. As Greek and Italian soldiers scrambled to defend crumbling ramparts, a young sultan watched from his horse on the hillside, silent and intent. His name was Mehmed. Soon, they would call him The Conqueror.

At just 21 years old, Sultan Mehmed II commanded an army of over 80,000 men, equipped with cutting-edge artillery and a determination no previous Ottoman ruler had matched. Across from him stood Constantinople, the proud capital of the Byzantine Empire, a city that had withstood more than a millennia of attacks. For centuries, its towering walls had been deemed impregnable. But Mehmed believed no fortress was invincible.

When the dust settled, the thousand-year-old Byzantine Empire was no more. But the fall of Constantinople didn’t just mark the end of an empire — it signaled the dawn of a new era.

Mehmed’s Early Life and Education

Sultan Mehmed II was born on March 30, 1432, in Edirne, the Ottoman capital at the time. He was the younger son of Sultan Murad II, and though his path to the throne was far from certain at birth, his education prepared him for greatness from the very beginning.

Following Ottoman tradition, his father assembled some of the empire’s finest minds to shape the young prince’s intellect and character.

His chief tutor was Molla Gürani, renowned scholar of Islamic law, who instilled in Mehmed both scholarly discipline and moral rigor and Akşemseddin, a celebrated Sufi mystic.

The extent of the young prince’s knowledge, however, far expanded just theology, and included jurisprudence and philosophy, ensuring he was deeply grounded in both religious and intellectual traditions. Beyond these, Mehmed displayed an insatiable curiosity for history, science, mathematics, and military engineering. Thanks to being a bit of a genius at languages, Prince Mehmed was also able to read classical works in original as he learned and spoke fluently Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Greek, and Latin, giving him access to the full breadth of medieval and ancient scholarship.

It was through these texts that Mehmed encountered the great figures of antiquity: Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and the Roman emperors.

In the young King of Macedon especially, Mehmed saw a conqueror who united vast territories under a single banner, crossing boundaries of culture and geography.

The young prince’s chance to rule came much earlier than expected. At just 12 years old, Mehmed was thrust onto the throne when his tired and depresse father, Murad II, abdicated.

His youth made him a target: rival factions stirred unrest, and probably even more importantly, foreign enemies probed the empire’s defenses, as King Wladyslaw II of Hungary and his famous general, John Hunyadi, began a new offensive in the autumn of 1444.

Under attack, the young Sultan supposedly summoned back his father with the following message: “If you are the sultan, come and lead your armies. If I am the sultan, I command you to return and lead them yourself.”

Murad returned to lead his son’s armies to victory at the Battle of Varna, while two years later, probably on the insistance of Grand Vizier Candarli Halil Pasha, he even returned to take power, and relegated his son to the governorship of the Manisa sanjak. The lesson was clear for young Mehmed: rulership was fragile, and authority had to be earned, not inherited. Mehmed never forgot it.

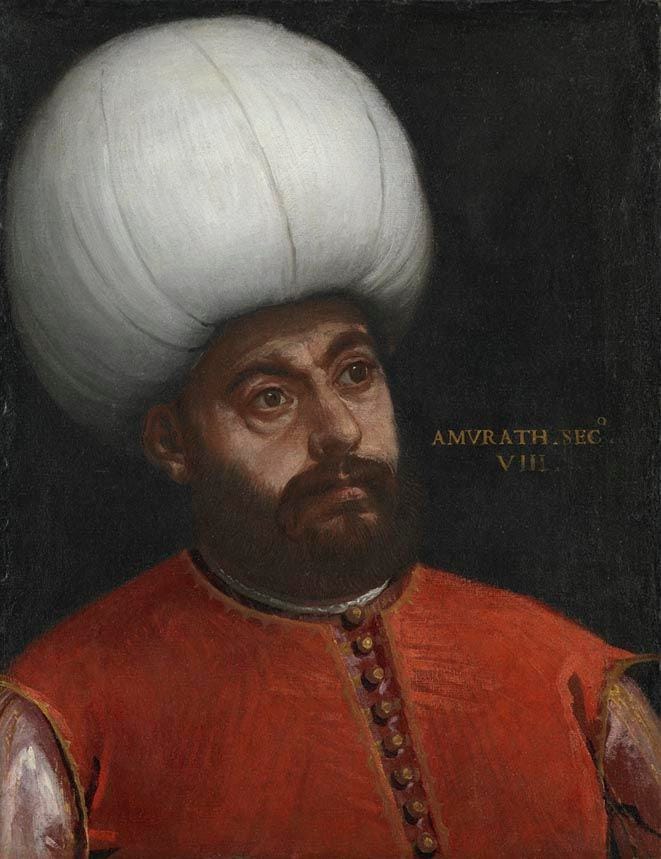

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Paolo Veronese. Sultan Murad II, the father of Mehmed the Conqueror.

The Road to Constantinople

When Sultan Murad II died in 1451, Mehmed II ascended the throne once more — this time as a man of nineteen, no longer a child monarch. The court in Edirne watched carefully.

Mehmed had returned to power with a singular purpose: to finish what generations of Ottoman rulers had failed to achieve.

The conquest of Constantinople wasn’t just a military objective; it was a political necessity. The Byzantine capital, though a shadow of its former glory, still controlled key trade routes and symbolized a Christian bulwark in the heart of Ottoman territory. As long as Constantinople stood, the Ottoman Empire remained incomplete — its lands divided between Europe and Asia.

Furthermore, though greatly reduced in land and wealth, the Byzantines had political tools of their own, as Ottoman refugee princes were sheltering in Constantinople, and if necessary could be used as potential threats to the Sultan by formenting civil war in the Ottoman Empire.

In theory anyway.

Once back in power, Mehmed wasted no time and paid little attention to the tools his enemies had. He began fortifying his position both militarily and diplomatically. In 1452, he ordered the construction of Rumeli Hisarı, a massive fortress on the European bank of the Bosphorus, directly opposite the earlier Ottoman fortress of Anadolu Hisarı.

With these twin fortresses, Mehmed could control naval traffic into the city and cut off any potential aid from the Black Sea. The scale and speed of the project shocked even his own advisors: Rumeli Hisarı was completed in just four months, its towering walls signaling to Constantinople that the siege was no longer a distant threat — it was coming. When the Byzantine Emperor protested, Mehmed coldly replied that he is no lord of any land outside the walls of his city.

At the same time, Mehmed secured peace treaties with Venice, other neighboring powers, isolating his enemy diplomatically to prevent intervention. Behind the scenes, he gathered an army of unprecedented size: some estimates suggesting numbering from 80,000 to 100,000 soldiers, including elite Janissaries, cavalry, and siege engineers.

But perhaps his boldest preparation was the commissioning of massive siege cannons, designed by the Hungarian engineer Orban. These guns were among the largest ever built in the medieval world, capable of hurling stone projectiles weighing over over a hundred kilogram at the city’s formidable Theodosian Walls.

By early 1453, the noose was tightening. By thisConstantinople’s population had dwindled to under 100,000, its walls crumbling in places, its treasury nearly empty. The Byzantine emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos sent desperate appeals for aid to the West, but the help that arrived was woefully inadequate to the challenge Constantinople had to fight off.

On April 6, 1453, Mehmed’s armies encircled the city. Siege engines rumbled into place. Cannons were aimed at ancient battlements that had withstood attacks for a thousand years. Mehmed’s gamble had begun — and he had staked his throne, his army, and his legacy on victory.

The Siege and Fall of Constantinople

At dawn on April 6, 1453, the cannons thundered and the siege of Constantinople began. For 53 days, Sultan Mehmed II’s forces battered the city’s famed Theodosian Walls, unleashing some of the largest siege guns ever constructed. Day after day, the bombardment shattered towers and bastions, yet the defenders refused to yield.

Inside the city, Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos relied not only on his native troops but also on a contingent of hardened Genoese mercenaries under Giovanni Giustiniani Longo, a skilled commander who led the defense of the city’s most vulnerable walls.

Giustiniani’s leadership and tactical expertise proved vital: he organized night repairs, directed sorties to sabotage Ottoman siegeworks, and personally commanded the key positions where the bombardment struck hardest. His arrival in Constantinople had lifted morale — but as the siege wore on, hope dimmed.

Mehmed knew time favored him. To outflank the defenders, he conceived an audacious plan: bypass the chain blocking the Golden Horn by hauling ships overland on greased logs. On April 22, to the shock of the Byzantines, Ottoman ships re-entered the harbor behind the chain, threatening the sea walls.

The fact that the Ottomans now threatened the sea walls also proved to be deadly to the defenders. Already overstretched, Giustiniani needed to further thin his weakening force..

Meanwhile, the great cannons continued to hammer the land walls. Yet despite the breaches, each Ottoman assault was repelled at heavy cost. Giustiniani and his men held firm, fighting in the dust and rubble as waves of Ottoman troops crashed against their positions in vain.

By late May even the Ottoman morale began to sunk, but the young Sultan was not prepared to give up just yet and ordered his men to prepare for a final, decisive assault.

On the night of May 28, as the exhausted defenders held a solemn religious procession in Hagia Sophia, Mehmed gathered his commanders. At dawn, the full might of the Ottoman army surged forward. Trumpets blared, war drums pounded, and the sky filled with smoke and arrows.

The initial waves of irregular troops and auxiliaries were beaten back. Then came the elite Janissaries, pressing the attack on the breaches near the Mesoteichion. In the chaos of battle, a pivotal moment unfolded: a small group of Ottoman soldiers discovered an unguarded sally port — the Kerkoporta gate — left open, possibly by defenders who had forgotten to secure it during the night’s confusion. Ottoman troops slipped through, seized the inner walls, and raised their banner inside the city.

At the same time, Giustiniani was gravely wounded while defending the land walls. His evacuation spread panic among the Byzantine ranks, weakening the defense at a critical moment. Seeing the Ottoman standard inside the walls, many defenders broke and began to flee.

Emperor Constantine XI was not among them. Refusing to abandon his post, is said to have cast aside his imperial regalia and charged into the melee, dying sword in hand alongside his remaining soldiers.

By mid-morning on May 29, 1453, the Ottoman army poured into the city. Mehmed entered triumphantly through the Gate of Charisius, pausing amid the ruins to survey his prize.

For Mehmed, it was more than a military triumph. It was the fulfillment of prophecy, the birth of a new imperial vision, and the moment he became “Fatih” — The Conqueror.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Fausto Zonaro. The entrance of Mehmed into Constantinople, the sight of his greatest victory.

The Siege of Belgrade (1456): The First Major Setback

After the fall of Constantinople, Mehmed II’s ambition reached new heights. With the Byzantine Empire wiped off the map, he sought to expand the Ottoman Empire into Europe. One of his next targets was the strategic city of Belgrade, a key fortress standing at the confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers, guarding the gateway to Central Europe.

In 1456, Mehmed laid siege to Belgrade with the same determination that had brought him Constantinople. He commanded an impressive force, reportedly around 100,000 men (though probably smaller in reality), including Janissaries, siege artillery, and skilled engineers. Belgrade’s defenders, however, would not yield without a fight.

The leader of the Christian coalition defending the city was none other than the famed John Hunyadi, former governor of the Kingdom of Hungary and now the voivode of Transylvania, one of the most accomplished military commanders of the age.

Yet Hunyadi’s task ahead was far from easy.

Once he received news the Ottomans might strike at Belgrade he already had the garrisson strengthened and sent his reliable ally, Michael Szilagyi, to take command, while he began to muster a field army of his own. Yet, due to the internal divisions in the country and lack of logistical support, Hunyadi’s forces probably numbered no more than 12,000 men, vastly outnumbered by Mehmed’s army.

The siege began in the summer of 1456, with Mehmed’s forces establishing a blockade around Belgrade’s formidable walls. Mehmed, confident in his superior numbers and artillery, prepared for a long siege. He ordered the construction of massive siege engines and cannons, much like those used in Constantinople. However, Belgrade’s fortifications, built on high ground and reinforced by years of experience in withstanding siege, proved resilient.

Mehmed’s approach was methodical, but the defenders, led by Szilagyi, put up a fierce resistance. A few weeks into the siege Hunyadi arrived in person also, and after defeating the Ottoman fleet on the river, he entered the city with his reinforcements.

Besides Hunyadi came another relief force also, led by the Francisan friar Giovanni da Capestrano, who assembled a large, but motley force of local peasants, numbering in the tens of thousands. Too large to be fed and ill-disciplined to man the walls, this force, however played no part in the defense of the fortress.

Once he deemed the walls sufficiently reduced, Mehmed ordered an all out attack, but the reinforced garrison proved too strong and repelled the attackers.

The turning point of the siege came a day later, when Capestrano’s motley force launched a suprise attack on the Ottoman camp. Watching from the walls, Hunyadi launched a daring attack of his own and captured the Ottoman cannons. Taken by surprise, the Ottomans found themselves on the defensive and barely managed to defend their camp and even the Sultan was wounded by a crossbow bolt to the thigh.

This defeat marked a rare blemish on Mehmed II’s record. It was the first time he had suffered a significant setback, and the failure to capture Belgrade delayed his ambitions in Europe for years.

Mehmed, however, did not let this defeat define him. He quickly recovered, redirected his efforts to other fronts, and continued to expand his empire and swiftly subjugated the remaining independent kingdoms of the Balkans— but the loss at Belgrade served as a reminder that even the most determined of conquerors can encounter setbacks.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons. The defeat at the siege of Belgrade was a rare setback for Sultan Mehmed II.

Mehmed as a Ruler and Reformer

While Sultan Mehmed II’s legacy is often defined by his military conquests, particularly the fall of Constantinople, his achievements as a ruler and reformer laid the foundations for the enduring strength of the Ottoman Empire. Mehmed’s reign was marked by a combination of legal innovation, cultural patronage, and administrative restructuring that ensured the empire thrived long after his death in 1481.

1. The Codification of Laws (Kanunname)

One of Mehmed’s most significant contributions was his development of a legal system that helped govern the vast Ottoman territories. While the Sharia (Islamic law) served as the spiritual and moral framework, Mehmed introduced the Kanunname — a codification of secular laws that addressed everything from land ownership to taxation and criminal justice. The Kanunname complemented Sharia, allowing the sultan to rule effectively over the diverse, multi-ethnic empire.

The implementation of these laws was not just about maintaining order; it was also a tool for centralizing power. Mehmed sought to curb the influence of regional lords and independent military leaders by tying the administration directly to the sultanate.

2. Patronage of the Arts, Architecture, and Intellectualism

Mehmed II was not only a master strategist and conqueror; he was also a patron of the arts, deeply interested in the intellectual and cultural advancement of his empire. His reign marked an early golden age of Ottoman architecture, literature, and art, which not only reinforced his imperial legitimacy but also blended Islamic and Byzantine influences. Mehmed recognized the power of culture as a tool of empire-building, and he invested heavily in the flourishing of Ottoman arts and intellectual life.

Architecture was a major focus of Mehmed’s patronage. His most significant architectural project was the construction of the Fatih Mosque in Istanbul, which became the centerpiece of the district bearing his name. This mosque was designed by the famous Ottoman architect Atik Sinan and symbolized both the spiritual and political power of the Ottoman state.

In addition to the grand mosque, Mehmed also commissioned the construction of numerous other buildings aqueducts, and palaces, all of which served to enhance the aesthetic and functional cohesion of his growing empire. These projects demonstrated his commitment to urban development and the transformation of Istanbul into the capital of a global empire.

Beyond architecture, Mehmed’s cultural influence extended to the arts. He was a patron of calligraphy, painting, and poetry. His court became a vibrant center for the preservation and creation of art. The sultan also commissioned a number of illuminated manuscripts and miniature paintings.

Mehmed also encouraged the development of literary culture. His court attracted numerous scholars, including those fleeing the fall of Constantinople. One of the most famous scholars to join Mehmed’s circle was the Greek philosopher George Amiroutzes, who had been a prominent figure in Trebizond before its fall.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Mehmed’s cultural patronage was his personal involvement in intellectual pursuits. He was known to be highly literate and possessed a deep interest in classical knowledge. Mehmed himself was a prolific reader, with a personal library that included works from both the Arabic and Greek traditions.

Mehmed was known to converse with scholars and philosophers at length, engaging in debates on topics ranging from political philosophy to theology.

In fact, one of his most significant intellectual endeavors was his efforts to preserve Greek and Roman knowledge. After the fall of Constantinople, many Greek scholars and manuscripts were brought to his court, where Mehmed provided protection and patronage. His personal interest in these classical works reflected his broader vision of the Ottoman Empire as the rightful heir to the legacy of Rome.

Mehmed’s cultural patronage was not just about the arts — it was also about the creation of an Ottoman identity. Through his investment in architecture, literature, and intellectual life, he cultivated a distinct cultural and political atmosphere that would shape the empire for centuries.

3. Consolidation of Power and the Janissary Corps

While Mehmed’s military exploits brought him fame, his ability to consolidate power in the empire was equally important. One of the key institutions that he strengthened was the Janissary Corps, the elite infantry force made up of devshirme (Christian boys taken from their families, converted to Islam, and trained as soldiers). These highly disciplined soldiers became a symbol of the sultan’s power and a central force in the empire’s military and administrative functions.

Mehmed’s reforms also included land redistribution, enhancing the sultan’s control over the empire’s resources. He increased the number of millet systems, granting religious communities a degree of autonomy in exchange for loyalty and taxes. This allowed for a degree of religious tolerance within his domains, fostering stability in an empire composed of various ethnic and religious groups.

4. A Vision of an Empire Beyond Constantinople

Mehmed’s ambitions were not confined to the conquest of Constantinople. He envisioned the Ottoman Empire as the rightful heir to the legacy of Rome and sought to establish Ottoman dominance across the eastern Mediterranean and beyond. This vision guided his military campaigns in the Balkans, Anatolia, and against the Mamluks in Egypt, expanding the empire’s reach and influence.

However, it was Mehmed’s ability to maintain unity in such a vast and diverse empire that cemented his legacy as one of the greatest Ottoman sultans. His leadership brought stability to the region, setting the stage for future rulers to expand upon his conquests.

Mehmed II’s Legacy

Sultan Mehmed II left an indelible mark on history, not only through his military victories but also through his visionary leadership that transformed the Ottoman Empire into a transcontinental superpower. His reign, which spanned from 1444 to 1466, set the stage for the empire’s enduring dominance in southeastern Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa.

1. The Birth of the Ottoman Empire as a regional superpower

Mehmed’s most immediate legacy is the dramatic expansion of the Ottoman Empire. By 1453, with the conquest of Constantinople, Mehmed effectively erased the Byzantine Empire from existence and established the Ottomans as the new power in the eastern Mediterranean. The conquest of Constantinople was not just a military victory; it symbolized the transfer of power from the East Roman Empire to the Ottoman Empire, heralding a new era for the Muslim world and the wider Mediterranean region.

Under his leadership, the Ottomans became a transcontinental empire, connecting Europe, Asia, and Africa. Mehmed’s campaigns in the Balkans, Anatolia, and the eastern Mediterranean ensured Ottoman dominance over key trade routes and established the empire as a formidable rival to other European powers, particularly the Habsburgs and Venetians. His conquest of Serbia and Bosnia in the 1450s solidified Ottoman control in the Balkans, while his continued push into Hungary in the 1460s laid the groundwork for further expansion in Europe. The Ottoman Empire emerged as the dominant political, military, and cultural force in southeastern Europe.

2. The Transformation of Constantinople into Istanbul

The fall of Constantinople was Mehmed’s greatest achievement, but its true significance went beyond the victory itself. After the conquest, Mehmed immediately began to transform the city, making it the capital of his empire and renaming it Istanbul. His decision to encourage the resettlement of various ethnic and religious groups, including Greeks, Armenians, and Jews, helped lay the foundation for the multicultural and multi-religious Ottoman society that would thrive for centuries.

The establishment of Istanbul as a center of culture, learning, and commerce ensured that it would remain a beacon of Ottoman power for over 400 years. Mehmed’s patronage of the arts, architecture, and scholarship in the city turned it into a hub for intellectual and artistic innovation. The Hagia Sophia, transformed into a mosque under Mehmed’s orders, would continue to symbolize the fusion of Christian and Islamic heritage that defined the Ottoman Empire’s identity.

3. The Ottoman Imperial System and the Legacy of Kanun

Mehmed’s reforms and consolidation of power laid the groundwork for the Ottoman imperial system, which would continue to function for centuries.

His Kanunname (the Code of Laws) became the basis for the legal structure of the Ottoman state. The Kanun balanced the authority of the sultan with the religious laws of Sharia, and it was instrumental in the administration a diverse and sprawling empire.

The millet system that Mehmed expanded allowed for religious communities to maintain a degree of autonomy, which was crucial in managing the empire’s diversity. This system, which granted religious minorities a degree of self-rule in exchange for loyalty and taxes, helped maintain internal peace and order in the empire throughout the centuries.

Imber, Colin ( 2019). The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power. Springer.

Nicolle, David (2001). Constantinople 1453: The end of Byzantium. Osprey Publishing.

Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. Tauris Publishers.

Qayser-i Rûm.