Emperor Charles V, arguably the most powerful ruler of the Habsburg Empire. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Lambert Sustris, Public Domain

For five hundred years, the House of Habsburg was among the leading dynasties of Europe, ruling over empires that spanned over the territories of more than a dozen modern states and, at one point, waging wars against half a dozen other European states.

At the height of their power, the patriarch of the Habsburg dynasty, Emperor Charles V, was the strongest ruler of Christendom and ruled over the first empire upon which the sun never set.

Charles V and his son Philip II are figures who are known by many people, even by those who are not necessarily interested in history. Far less well-known are the figures who laid down the foundations for the power of the Emperor or King Philip II, but I believe their story, in many regards, is just as interesting.

The road of the Habsburgs from a minor Swiss noble house to the dominant dynasty of Europe is, without doubt, one of the success stories of late Medieval and Early Modern Europe.

Early rise

Little certain is known about the origins of the Habsburgs. It is believed that Gunthrum the Rich was the dynasty’s founder. Under him and his successors, the Habsburgs grew into one of the richest noble houses in the region thanks to the trade flowing between Italy and Germany.

By the late 11th century, the patriarch of the dynasty Otto became the first Count von Habsburg, signaling the elevation of the family into the elite of the Empire.

The rise of the Habsburgs continued in the 12th and 13th centuries when they allied themselves to the Hohenstaufens, the family that held the Imperial title from the middle of the 12th century.

Thanks to their alliance with the Hohenstaufens, the Habsburgs received lands in Swabia and became an influential family there also.

The opportunity to rise further came in the second half of the 13th century. The Hohenstaufen dynasty became extinct on the male line in 1254, and a twenty-year interregnum followed when the imperial electors failed to elect a new Emperor.

Rise and division

This interregnum was a period of chaos and anarchy. But as always, chaos can be an opportunity for advancement, and nobody used it better than Rudolf, the head of the Habsburgs. By 1273, the imperial electors had enough of the interregnum and settled on a compromise candidate for the Imperial title, Rudolf von Habsburg.

He was the ideal candidate, as he was rich and influential but not powerful enough to threaten the rule of his allies in their own lands.

His election, however, was not well received by Ottokar of Bohemia, the most powerful ruler of the empire. During the chaotic years of the interregnum, Ottokar carved out a mighty landmass inside the Holy Roman Empire and was eyeing up the Imperial title for himself, but the electors felt themselves threatened and rather backed Rudolf.

Conflict soon broke out between Ottokar and Rudolf. With the assistance of some princes and the King of Hungary, Rudolf defeated Ottokar, who died on the battlefield.

Following his rival’s death, Rudolf seized the duchy of Austria for himself, lands held previously by Ottokar.

Rudolf reigned for another fifteen years after the death of Ottokar and tried his best to reestablish some order in the empire, but his efforts met only with limited success.

As Rudolf was never crowned by the Pope, he remained only the King of Germany during his rule, not the Emperor, and thus he was unable to nominate his heir. He tried his best to secure the title for his son Albert, but the princes rather voted for another candidate, the Duke of Nassau.

Albert eventually was elected King in 1298, but this came as a result of the disaffection of the princes with the previous King, who was deposed after he angered too many men.

Albert ruled as King until 1308, but just like his father, he never managed to go to Rome and get himself Crowned by the Pope. Thus he was also unable to nominate his own heir, and the Imperial title slipped out of the grasp of the Habsburgs for 130 years.

Between 1308 and 1438, the family’s position can be described as stagnant. Albert’s successors solidified the control of the family over their lands in Austria. However, they failed to expand, and by the time the family regained the Imperial title, they had lost all their lands in Switzerland.

The family also saw itself become divided into many branches in the late 14th century when the brothers Albert and Leopold agreed to divide the family lands among themselves. In the following decades, the Leopoldine branch of the family was further divided into the Styrian and Tyrolean lines.

Initially, it was the Albertine branch that did the best with its limited resources. They formed a close alliance with the Luxembourg dynasty that ruled Bohemia, Hungary and occupied the Imperial throne. Emperor Sigismund Luxembourg had no male heirs, and he chose Albert, head of the Albertine branch, as his heir and married his daughter to Albert.

Albert succeeded Sigismund in 1437, but his reign was brief, as he died two years later while he was campaigning against the Ottomans.

Albert’s wife was pregnant when he died, but as there was no heir when he died, a succession crisis erupted.

The Hungarian magnates elected a rival King, Wladyslaw of Poland. Albert’s wife fled the country and sought assistance from Frederick, head of the Styrian branch of the family, but the wily and calculating Frederick chose to use Albert’s son as a hostage when the boy was born.

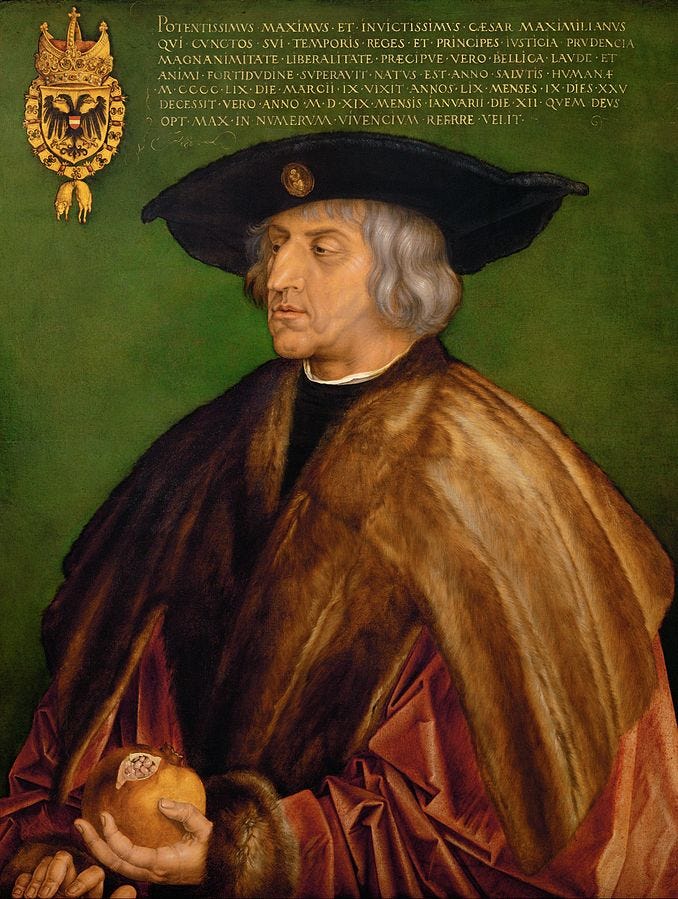

Emperor Maximilian (1493–1519) was one of the most ambitious and dynamic of the Habsburg rulers, and it was due to his fortuitou smarriage alliances that the family gained the thrones of the Spanish Kingdoms. Maximilian also tried to reform the institutions of the Holy Roman Empire to strengthen his own power at the expense of the imperial princes, though his efforts were largely frustrated by the princes. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Albrecht Dürer, Public Domain

Reunification

Between 1440 and 1452, Frederick used young Ladislaus( the son of Albert) as a hostage, ruling his domains in the boy’s name. He was forced to give up the boy in 1452 when a coalition of Hungarian and Austrian nobles besieged him in his residence. Still, fate presented another chance for Frederick to annex the Albertine lands five years later when young Ladislaus died without an heir.

Frederick, his younger brother, and the head of the Tyrolean line fought over the inheritance in the following years. Frederick was initially defeated by his brother, but conveniently for Frederick, he died before claiming the inheritance. With the assistance of the Pope, Frederick got the better of Sigmund, his Tyrolean adversary, and claimed the Albertine inheritance.

Still, despite his successes, Frederick faced many adversities in the last two decades of his reign. In the 1470s, he came into military conflict with Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, and the formidable Black Army of the Hungarian King overran much of Frederick’s Austrian lands in the 1470s and 1480s, even conquering Vienna, the Imperial capital of the Habsburgs.

The opportunity to rise came through marriage rather than the force of arms for Frederick.

Following Albert’s death, Frederick was elected as King, and, in 1452, crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. The prestigious title came with many advantages, which the Habsburgs used in the 1470s.

During this time, Charles the Bold of Burgundy was rapidly expanding in Alsace, Lorraine, and the Low Countries, creating a continuous empire stretching from the North Sea into the Alps. The ambitious Duke wanted to further elevate his house by securing the prestigious royal title of King for his family, but only the Emperor had the power to fulfill this desire.

As Charles had no male heir, Frederick negotiated a deal with the Duke. In exchange for a marriage between his son Maximilian and Charles’s daughter, he agreed to the Duke’s demands.

Unfortunately, the Duke was killed in battle before any of this could have happened. Following the death of Charles, a succession crisis erupted in Burgundy, and the Habsburgs and the Valois ruling France fought over the Burgundian inheritance, partitioning it in the end.

The Habsburgs failed to secure the entire inheritance but held on to the rich Low Countries, which propelled them to become one of the richest dynasties in Europe.

Luck shined on Frederick and Maximilian again in the early 1490s when Sigmund of the Tyrolean branch agreed to name Maximilian as his heir, leading to the reunification of the Habsburg lands.

Height of power

By the time Frederick III died in 1493, his heir Maximilian was in control of the Habsburg hereditary lands, and his son Philip was the Duke of Burgundy.

Though Maxilian never really succeeded in making himself accepted in Burgundy, his son Philip was securely in power, and Philip’s descendants were in line to unify the Habsburg’s lands.

Thanks to their control of Burgundy, the Habsburgs became potential allies for the Kingdoms of Castille and Leon, the alliance, of course, aimed against the expansionist ambitions of the French.

A double marriage alliance was secured in the 1490s when Prince Juan married Princess Margaret, while Philip of Burgundy married Princess Joanna.

Luck shined on the Habsburgs again when Prince Juan died shortly after his marriage. Juan was the only son of the Catholic Monarchs, and next in line for the succession was Joanna, the wife of Philip.

Queen Isabella of Castille died in 1504, and she named Joanna as her heir, but according to her will, if Joanna was in no state to rule due to her mental instability, it was to be Ferdinand, Isabella’s husband, who ruled as regent until Joanna’s heir Charles came of age.

Following Isabella’s death, a succession battle erupted between Ferdinand and Philip, and with the backing of the Spanish nobility, Philip forced Ferdinand to leave Castille, but his early death in 1507 led to Ferdinand’s return a few years later.

Still, as Ferdinand had no heirs when he died in 1516, he was forced to name Charles of Ghent as his heir.

Thanks to the Spanish inheritance, by 1516, Charles was the Duke of Burgundy, the King of Castille, Aragon, and Navarre already. His list of titles grew further in 1519 when his grandfather Maximilian died.

Thanks to large bribes and the help of the wealthy Fugger family, Charles was elected as Emperor in 1519, and the Habsburgs well and truly became the most powerful dynasty in Christian Europe.

Two further titles fell for the Habsburgs in 1526 following the Battle of Mohacs. King Louis of Hungary died in the aftermath of the battle, and he had no heirs, so a succession crisis erupted in Hungary.

The divided nobles elected two Kings, one of these figures being Archduke Ferdinand, the younger brother of Emperor Charles. Louis was also the King of Bohemia, and the Bohemian nobility rallied to Ferdinand’s cause, securing yet another title for his illustrious family.

Source

Curtis, Benjamin (2013). The Habsburgs: The History of a Dynasty. Bloomsbury Academic