From Power to the Executioner’s Block: The story of Flavius Stilicho

The half-Roman general who kept the Western Empire afloat

For over a decade, Stilicho was the shield of the Western Roman Empire, standing between Rome and the storms of invasion, rebellion, and chaos. A capable general and shrewd politician, he kept the empire together as it teetered on the brink. Yet his life ended in betrayal and execution, leaving a legacy as fragile as the empire he fought to preserve.

A depiction of Stilicho and his family. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Carlodell, CC BY-SA 4.0

Early life

Flavius Stilicho was born around 360 AD, though the exact date is lost to history. His lineage, however, is telling: the future strongman of the Western Empire was the son of a Vandal officer in Roman service and a Roman noblewoman. Their names have not survived, but the doors opened for Stilicho in the 380s suggest they were people of standing.

It’s interesting that the man who would later shape Western politics first became known in the East, serving under Emperor Theodosius I. Theodosius took power in 379, right after Rome’s crushing defeat at Adrianople, where Emperor Valens died. His first campaigns against the Goths didn’t go well either. By 380, his new army had been defeated, so he had to depend on generals sent from the West by his co-emperor, Gratian.

Whether Stilicho fought in these early wars is uncertain. At best, in his early twenties, he could only have served as a junior officer. His real breakthrough came later in that decade, when fortune and politics combined in his favor: Stilicho married the adopted daughter of Theodosius and was made commander of the Emperor’s household guard. The match bound him to the imperial dynasty itself, and Theodosius even recognized Stilicho’s son, Eucherius, as his own grandson.

Though sources are silent on Stilicho’s role in Theodosius’ campaigns of the 380s — against the Goths in 386 and the usurper Magnus Maximus in 388 — his position as commander of the guard makes it likely he was present. His first confirmed opportunity for real field command came in the early 390s, after the death of a senior general in a Gothic ambush. Stilicho stepped into his place as magister militum, just as Theodosius was preparing another march into Italy to topple a usurper.

This new campaign was born out of the chaotic politics of the West. After Magnus Maximus’ defeat, Theodosius restored Valentinian II. In reality, the boy was a mere puppet in the hands of his general, the Frankish magister militum Arbogast.

The relationship between the two turned poisonous quite quickly. When Valentinian tried to dismiss his overbearing commander, Arbogast reportedly tore up the letter in his face, telling him bluntly: “I did not receive my power from you, and you cannot take it away.”

Humiliated and powerless, Valentinian hanged himself in 392 — or so the official story claimed. Rumors quickly spread that Arbogast had murdered him, but the truth may be simpler: a teenager crushed by the weight of an empire and the contempt of the man who was truly pulling the strings.

Though we may never find out the truth about the death of Valentinian II, suicide was probably more likely than murder. Being a Frank, Arbogast had no path to the purple himself. Furthermore, he was left in command in the west because, up to that point, he had proven himself loyal to Theodosius, who trusted him fully, and there was no hint in his earlier actions that he would betray his master.

In addition, the death of Valentinian was almost certain to bring him into conflict with Theodosius. On the one hand, the Emperor was married to the sister of Valentinian II, and was said to have grown fond of his young wife, who would no doubt blame Arbogast for the death of his brother. On the other hand, as he could not claim power for himself, even if he was ambitious, Arbogast had to raise a figurehead to be the Emperor, while he was pulling the strings from behind. Something that he was already doing under the re-instated Valentinian II.

From this perspective, Arbogast had little to gain by removing Valentinian II, but a lot to lose.

After months of negotiations with Constantinople, Arbogast raised a bureaucrat called Eugenius as the new Western Emperor, but still tried to maintain peace with the East.

Theodosius, however, chose war. In 393, he made his younger son, the boy Honorius, Augustus, and in 394, he marched west, this time with Stilicho at his side. The campaign culminated in September at the Battle of the Frigidus, a bloody two-day clash in the Julian Alps.

Arbogast proved himself a much better general than Theodosius, and he put his opponent in a very difficult position. At first, the eastern army was thrown back, suffering heavy losses in costly frontal assaults, as there was no other way to attack the western army in the valley, thanks to Arbogast carefully blocking other entrance points.

But on the second day, Theodosius got a lucky break. During the night Arbogast sent soldiers to move behind the eastern army and block its exit from the valley. Rather than execute their orders, however, these troops promptly deserted. Than Mother Nature intervened.

As the armies prepared to engage, a fierce wind blew directly into the faces of the western army. Chroniclers claimed it was so strong that the Westerners’ missiles were flung back into their own ranks. Whether miracle or coincidence, the result was the same: the western line collapsed, Eugenius was captured and executed, and Arbogast fled, only to take his own life days later.

Theodosius had won. For a brief moment, he ruled as sole emperor of Rome — the last man ever to do so. He did not live long to enjoy his victory, though, and by January 395, Theodosius himself was dead, leaving behind a divided empire and a dangerous power vacuum. Into this void would step Stilicho, the imperial son-in-law who now stood at the center of Roman politics.

Emperor Theodosius I, the man in whose service Stilicho rose to power. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, Anthony van Dyck

An unlikely mandate?

The Roman world of early 395 looked nothing like it had a year before. In January 394, Theodosius ruled the East, while the West was in the hands of Arbogast and his protege Eugenius. By the start of 395, all three were dead. In their place stood two boys: Arcadius, barely eighteen, in Constantinople, and his nine-year-old brother Honorius in Milan.

On paper, there was no succession crisis. Both sons had already been crowned Augustus during their father’s lifetime. But in practice, neither was old enough to govern. Real power would fall to those who ruled in their names. The only question was — who?

In the West, the answer seemed obvious. Stilicho was not only a senior general, but also bound by marriage to the imperial family. According to Stilicho himself, Theodosius had named him guardian of both his sons on his deathbed. There was just one problem: no one else heard it.

With no witnesses and no formal documents, Stilicho’s claim rested on little more than his word.

Fortunately for him, his command of the army gave that word weight. In the West, his authority was accepted. In the East, things played out differently. There, power gathered not in the hands of a general, but of a senior bureaucrat called Rufinus, who quickly became the guiding hand behind the young Arcadius. Yet Rufinus faced a weakness Stilicho did not: he had little sway over the army (the Balkan field army being stationed in Italy of all places, under the command of his rival), at a moment when military strength became the currency of survival in a fractured empire.

For the moment, two rival guardians of empire coexisted uneasily — Stilicho in the West, Rufinus in the East. But it was only a matter of time before their competing claims to authority brought them into direct collision, with the fate of both halves of the Roman world hanging in the balance.

The “Cold War” Between East and West

In the opening months of 395, Stilicho made a fateful decision: he disbanded the barbarian foederati who had fought under Theodosius in the campaign of 394 and ordered them home. Instead of quietly returning to their settlements in the Balkans, the Goths proclaimed a new king — Alaric — and promptly rose in rebellion. With the Balkan field army still stationed in Italy, Alaric seized his moment. He marched unopposed into Thrace and advanced all the way to the walls of Constantinople.

Alaric, however, had no real intention to attack the city, and in reality, he was playing a different game. He camped beneath the city’s defenses and used his army as leverage, demanding official recognition and high rank in the imperial hierarchy. Rufinus, Arcadius’ chief minister, found himself in an impossible position. With no field army at hand, he could not force Alaric away, and so he chose negotiation. The Goths were bought off and led away from the city, but their rebellion was far from over. According to Stilicho’s spin doctor, Claudian, Rufinus even allowed Alaric to ravage the Balkans if only he departed, though this claim may have been a simple lie, knowing who Claudian’s paymaster was.

Stilicho, hearing of the chaos, marched to the Balkans and confronted Alaric directly. According to Claudian, Stilicho cornered the Gothic king, virtually surrounding him and holding him at his mercy — until orders arrived from Constantinople. Stilicho was commanded to halt, return to Italy, and send the eastern field forces back to Arcadius. Reluctantly, he obeyed.

The decision had immediate consequences. When the eastern army arrived in Constantinople, Arcadius and Rufinus went out to greet its commander, the Gothic general Gainas. Before the Emperor’s eyes, Rufinus was hacked to death by the soldiers. Whether Stilicho orchestrated this assassination is impossible to say. On one hand, Rufinus’ death removed a rival who had blocked Stilicho’s claim to be the guardian of Arcadius. On the other hand, Stilicho gained little, for Rufinus was swiftly replaced. New figures — first the eunuch Eutropius, later Gainas himself — rose to dominate the eastern court and frustrate Stilicho’s ambitions.

Meanwhile, Stilicho turned his attention back to the western frontier. In 396, he campaigned along the Rhine, only to return to the Balkans the following year for another showdown with Alaric. Yet again, the Gothic king slipped from his grasp. Worse still, the balance of power had shifted. Eutropius brought Alaric into the eastern army, legitimizing his position and ensuring that Stilicho, reliant only on his western forces, could no longer act decisively against him.

Furthermore, by now, the roles of 395 have also been reversed. Two years earlier, Alaric was a rebel who was tormenting the Balkans, and Stilicho could claim to act in the name of the empire as its protector. In 397, Alaric was a Roman general, and the actions of Stilicho were very hard to sell or explain to the eastern court. Arcadius lost no time in taking decisive action. He denounced Stilicho as a public enemy and confiscated his property, signaling just how poisoned relations had become. The West’s most powerful general now stood branded a traitor in the eyes of the East.

Even more dangerous was the crisis brewing in North Africa. The province was the breadbasket of Italy, and its governor, Gildo, declared loyalty to Constantinople, threatening to starve Rome itself. Even at the best of times, the city was volatile, and food shortage was more or less a straight path to riots. Riots in themselves were not the end of the world, as using the army, Stilicho could quell them, though probably at quite some cost in human life. If some important political figure were to use the mob to his own advantage and stand up against Stilicho also (and the whole Senate was in Rome) and try to rally support, the life of the generalissimo was instantly much more complicated.

The defection placed Stilicho in an existential bind. To shore up his position, he arranged a marriage between his young daughter Maria and Emperor Honorius, binding his family even closer to the imperial dynasty.

Stilicho also decided to act with speed, though indirectly. Instead of leading the campaign himself, he dispatched Gildo’s estranged brother, Mascezel, to confront the rebel. Mascezel moved swiftly, defeating Gildo in a lightning campaign that ended with the governor’s suicide. On his return to Italy, Mascezel basked in honor and acclaim. Yet according to the later historian Zosimus, Stilicho grew jealous of his subordinate’s popularity and had him quietly killed within months. If true, the episode casts a dark shadow on Stilicho’s character — but caution is needed. Zosimus, writing more than a century later, was no friend of Stilicho in his writing.

Whatever the truth, Stilicho emerged from the African crisis strengthened. Rome’s grain supply was once more secure, and the rebellion crushed. With Rufinus gone but new rivals entrenched, Stilicho’s dream of acting as guardian to both Arcadius and Honorius was lost. For the next eight years, relations between East and West were volatile, and Stilicho abandoned any serious designs on the eastern court. His power became firmly fixed on the West.

The Defender of the West

Stilicho’s strained relations with the East might have eased had circumstances turned out differently. In 399, Eutropius was toppled after bungling a military crisis. For a moment, power in Constantinople fell to the Gothic general Gainas, but his reign was brief. Within months, he was driven out of the capital, chased across the Danube, and finally executed by the Hunnic warlord Uldin. His fall cleared the stage for another Gothic general, Fravitta, who emerged as the new strongman in Constantinople.

One clear loser in these shifting intrigues was Alaric. Under Eutropius, the Gothic king had secured a commission in the imperial army. His successors revoked it, stripping him of rank, pay, and supplies. Squeezed by broken promises and dwindling resources, Alaric turned west.

In the autumn of 401, he invaded Italy. Stilicho, campaigning against the Vandals beyond the Alps, was trapped on the far side of snowbound passes, leaving northern Italy exposed. Alaric struck boldly, besieging Mediolanum, the residence of Emperor Honorius himself. Not until the spring thaw of 402 could Stilicho march south to meet him.

When he did, the clash was fierce. Stilicho fought two pitched battles — first at Pollentia, then at Verona — beating Alaric each time and finally driving him from Italy. Yet the Roman victories were incomplete, and the Gothic leader was not destroyed. Despite defeats, the loss of his loot, and desertions, Alaric survived. Some suggest Stilicho cut a quiet deal with him in 402: Alaric would leave Italy unmolested, in exchange for a rank in the Roman army. When this deal may have been made is an interesting question; 402 is a possible date, though some suggest it may have happened later, as late as 405, when Alaric and Stilicho exchanged hostages as a sign of good faith, one of the Roman hostages being a young Flavius Aetius.

Whatever the truth, Alaric made no further attempt to invade while Stilicho lived — a silence that hints at an understanding.

That silence proved crucial when another threat arrived. In late 405, a vast host under the Gothic king Radagaisus descended upon Italy. Unlike Alaric, Radagaisus brought an overwhelming force. His invasion was so large that Stilicho dared not risk a pitched battle until reinforcements arrived from Gaul and mercenaries were raised abroad. For six anxious months, he gathered strength while Radagaisus pressed forward, even laying siege to Florence.

Stilicho’s patience was rewarded. By the summer of 406, he had a force strong enough to challenge the invader. Radagaisus, for his part, made a fatal mistake. To ease supply shortages, he divided his massive army into three separate groups. Stilicho seized the opportunity. The Roman army moved swiftly, forcing Radagaisus to abandon the siege of Florence and trapping his core force at Fiesole. Hemmed in and desperate, the Gothic king tried to escape (or alternatively ride to the other two groups and lead them to his blockaded force), but was captured and executed in August 406.

Leaderless, his men capitulated. Twelve thousand warriors were drafted into the Roman army; the rest were sold into slavery.

This was Stilicho’s greatest achievement. He defended Italy against repeated invasions, protected the emperor, and won victories that few Roman generals of his time could equal. Still, for Stilicho, triumph in 406 marked the beginning of his swift decline.

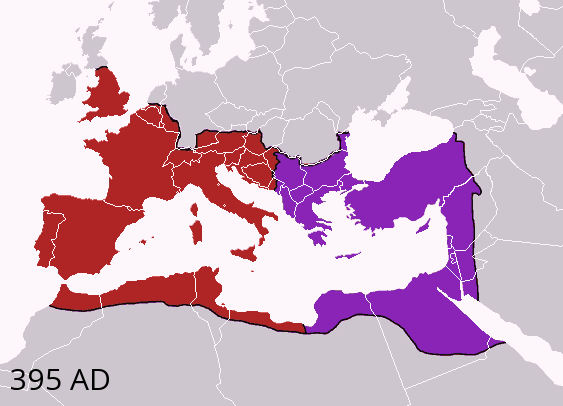

The empire in 395, when Stilicho took power in the West. By the time the city of Rome was sacked in 410, Britain and much of Spain had been lost. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Fall of Stilicho

The influx of 12,000 new recruits after Radagaisus’s defeat seemed to put Stilicho at the height of his power. With a reinforced army and Alaric as a willing partner, he prepared to march east. His goal was modest compared to earlier ambitions: reclaim a handful of provinces in the prefecture of Illyricum, provinces that traditionally belonged to the west until Gratian transferred them to Theodosius to ease the latter’s struggle against the Goths. These rugged lands were no treasure chest, but they had always been fertile recruiting grounds for Roman soldiers — and Stilicho, who struggled for recruits in the west, may even have given a promise to Alaric, naming the Gothic King commander of Illyricum.

If true, it was a shrewd plan, as in one swift move, Stilicho was to gain a battle-hardened army and fertile ground to recruit more men.

But just as Stilicho’s plans were coming together, unexpected events disrupted everything.

In Britain, the legions mutinied in 406, elevating a general named Marcus as emperor. He was soon murdered, replaced by Gratian , who shared the same fate within four months. Finally, a third usurper rose: Constantine. Unlike his short-lived predecessors, Constantine was there to stay.

Meanwhile, Stilicho’s decision to strip the Rhine frontier to strengthen Italy had opened the floodgates. Brushing aside the Frankish foederati defending the Rhine, a large force of Vandals, Alans, and Suevi surged into Gaul.

At first, Stilicho underestimated the crisis and only dispatched a force of Pannonian Vandal foederati to strengthen the Gallic army. Locals, however, shut the gates in front of the reinforcements, who were reduced to plundering the countryside for supplies. Not much later, they defected to the invaders.

While events were unravelling in Britain and Gaul, Stilicho seemed oblivious to the scale of the trouble, and ordered Alaric into Epirus, while he was preparing the now enlarged army of Italy, gathering ships in southern Italy to join Alaric in the summer. As Stilicho was seemingly ignoring Gaul, the usurper Constantine crossed the channel and rallied the garrison of Boulogne to his cause and destroyed a group of Saxon raiders, who were plundering the coasts.

Constantine was not wasting time on the coast either, and rapidly began to march south with his army, capturing modern-day Lyon a few months later, and began to mint coins there. The movement of a large Roman force caught the attention of the Rhine invaders also, who also began to move east towards the Rhine, where they sacked Strasbourg. Apparently, there was not much fighting between Constantine and the invaders, and the usurper secured peace through diplomacy. The rise of this powerful usurper finally forced Stilicho to abandon his Balkan ambitions, and the campaign of 407 was called off.

Thanks to the logistical difficulties in transporting such a large force from one place to another, a campaign in Gaul was now out of the question, and Stilicho dispatched only a small force to Gaul, led by Sarus, a Gothic chief who joined the Roman army probably after Alaric’s 401–02 invasion. The main Roman army was ordered to take station at Ticinum, from where they would launch an attack in 408.

Sarus was initially very successful in Gaul and scored some early victories, killing two of Constantine’s generals and besieging the usurper himself. But when another of Constantine’s generals, Gerontius, arrived with a powerful relief force, Sarus had no choice but to retreat — selling off his plunder just to cross the Alps in safety.

Despite this setback, the campaign had shown that Constantine was vulnerable. Stilicho, now gathering his full army at Ticinum, hoped to crush him in 408.

Once again, unexpected events changed everything.

That spring, Alaric appeared on the doorstep of Italy demanding payment. At first, his demand looked like extortion. But Alaric had spent the past year stranded in Epirus — waiting in vain for Stilicho to arrive — while bleeding treasure to feed and pay his men. To raise the 4,000 pounds of gold on such short notice, however, Stilicho needed the support of the Senate, and a meeting was called in the early months of 408.

At first, the Senators and Emperor Honorius were outraged, and a first vote flatly rejected the subsidy. Then intervened Stilicho, who confirmed that Alaric was acting under his orders and saw his case as legitimate, and urged the Senate to meet Alaric’s price. Many Senators balked, one going so far as denouncing it as a “pact of servitude,” but Stilicho prevailed. The money was raised, and war was averted — for now.

Then came devastating news: Emperor Arcadius of the East was dead. His heir, Theodosius II, was only seven years old. Honorius, now the senior Augustus, wished to sail east and safeguard his nephew’s succession. Stilicho persuaded him otherwise, volunteering to go himself. But while emperor and general wrangled over the future of Constantinople, the menace of Constantine in Gaul grew ever more urgent.

By the summer of 408, Stilicho’s army was assembled, but delays piled upon delays as neither the campaign into Gaul nor Stilicho’s journey east materialized.

Worse, the emperor and generalissimo drifted apart, leaving a dangerous vacuum. Into that space stepped Olympius, a court bureaucrat with a talent for intrigue.

Originally a creature of Stilicho, for some reason, Olympius decided to turn against his former patron, and he began to spread rumors that Stilicho planned to make his son, Eucherius, the new Eastern emperor, constantly having the lie repeated at the camp in Ticinum.

The poison worked. On August 13, while Honorius reviewed the army at Ticinum, the soldiers erupted in mutiny. In what can best be described as a carefully orchestrated coup, the officers and civilian officials loyal to Stilicho were butchered in front of the powerless emperor. Curiously, however, Honorius was left untouched while his officials were murdered at his feet.

News soon reached Stilicho, who was encamped with his bucelarii and foederati at Bononia. At first, his allies urged him to retaliate, and Stilicho agreed, planning to teach a lesson the mutineers were not to forget.

Yet when he learned that Honorius was unharmed, Stilicho became hesitant. The reaction was understandable. If the Emperor had been murdered, Stilicho would have been facing simple usurpers. With Honorius alive, however, the situation was potentially even more dangerous. By now, Emperor and generalissimo have been in disagreement quite frequently, with Stilicho getting his way regarding the payment of money to Alaric and the voyage to Constantinople also, but perhaps at long last, Honorius lost patience with Stilicho and decided to throw him under the bus.

Alternatively, the mutiny may have been the work of ambitious men, who, lacking any legitimacy of their own, could not take power in their own name, thus moved to remove the power behind the throne of Honorius and fill the position themselves. In this scenario, the Emperor was now only a helpless pawn in the hands of Stilicho’s enemies.

Furthermore, if the two parts of the Roman army were to fight each other, even the winner would incur losses, losses they could scarcely afford with a usurper gaining strength just across the Alps.

Looking at the situation from this angle, Stilicho’s caution was understandable. This restraint, however, was to cost him dearly, as while the generalissimo was vacillating and trying to figure out who his real enemies were, Sarus turned on him, murdering Stilicho’s Hunnic bucelarii in their sleep.

With his personal guard now gone and not knowing who he can trust anymore, Stilicho fled to Ravenna and ordered the garrison to bar the entrance and under no condition allow the foederati to enter the city. Expecting orders of his arrest to arrive at any moment, Stilicho took refuge in a church, no doubt hoping his enemies would respect sanctuary.

On August 23, he was coaxed out under a false promise of safety. Yet the moment he stepped out of the church, he was shown a second imperial letter, ordering his immediate execution.

Remaining a loyal servant of the empire to the last, Stilicho refused to fight or try to escape and ordered his remaining men to stand down, facing his death with great courage and dignity.

Who was Stilicho?

Being the de facto leader of the Roman West for 13 years, Stilicho oversaw the defense of the empire well until the Crisis of 406, especially when one considers several disadvantages he had.

Firstly, despite becoming the leader of the West, he was not from the West and arrived only a few months earlier, and initially had no real power base of supporters. Secondly, the western armies were also in a poor state following the two defeats in the civil wars of 388 and 394, western losses being especially high in 394, at the decisive Battle of the Frigidus River. Lastly, though he was the power behind the throne of Honorius, Stilicho was not the Emperor, nor was he a regent in the modern sense of the world, as no such thing existed in late Rome.

Yet despite the victories Stilicho enjoyed up to 406, one still cannot look past the fact that his fixation on the Balkans led to disaster, and the crisis on the Rhine frontier allowed the rise of a usurper who snatched Britain, Gaul, and Spain from Honorius.

Ultimately, however, from my point of view, Stilicho was more unlucky than incompetent in the handling of the crisis that erupted in late 406. The speed of ancient communications being what they were, by the time the gravity of the situation became clear in Italy (especially regarding the usurpers in faraway Britain), it may have been too late to rectify it.

Sources:

Heather, Peter (2005). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press.

Hughes, Ian (2010). Stilicho: The Vandal Who Saved Rome. Pen and Sword Military